Time to step on the geek soapbox. I have a topic that so fully stirs my nerdy passions that I will not only discuss it with anyone willing to listen, but I will flat out rant about it with melodramatic fervor. It’s a topic that bares no true impact on my existence, but nonetheless riles me, and if one breathes a word that could justify me bringing it up they best believe I will stand on that soapbox and holler for all the world to hear.

I loathe unfaithful film adaptations of graphic novels.

Before I launch into this, I should probably explain where I’m coming from. Although I am a late-in-life fan of comics who didn’t start reading them until my freshman year of college, I am an avid one. I could tell you all about how Robert Crumb’s work with comix in the 1960s served as cultural catharsis for a generation of young males lost in a rapidly changing culture. I can break down how Neil Gaiman has utilized classic story telling and brilliant artists to broaden the popular reach of the comic art form. And naturally, I can tell you all about the difference between a comic and a graphic novel.

Over the years I’ve come to see a comic as a story that is one author’s take on a basic character concept. Generally these books have an open-ended nature to their conclusion; the events of this particular tale may have been resolved, but they are far from forgotten. Adherence to the continuity of the character’s world and the events that affect the characters therein is of vital importance. Although authors can play around wildly with the ins and outs of their narrative, they ultimately have their creative hands tied by the restrictions of working in a constantly evolving world. Essentially, a comic book author can send Spider-Man into the heart of a complicated battle with Green Goblin, but at the end of the day he will triumph over but not ultimately defeat his foe, and he will still be going home to Mary Jane.

A graphic novel on the other hand is a fully fleshed-out, stand-alone story with a closed, definitive ending. Graphic novel authors may choose to write about characters that are extremely well-known, but because their stories are stand-alone in nature they tend to involve outrageous or even shocking takes on the mythos of their protagonist. Several editions may be required to complete the story, but at the conclusion they have definitively ended with a finality that rarely exists in the comic realm. Finally, the graphic novel author’s creation stands either outside or alongside a character’s general canon. For example, The Long Halloween is a piece that follows the Batman universe faithfully in terms of both the traditions and characterizations, but the actions within and conclusion to the story are not considered part of what readers think of as Batman’s constantly evolving back-story.

While both of these comic forms have amazing, highly respected works associated with them, one seems to be much harder to nail as an on-screen adaptation. I can count on one hand the number of truly successful graphic novel adaptations when judged on box office gross, critical acclaim, and lack of fanboy flack. In comparison, there are countless good, if not great, comic book inspired movies. This is because the Hollywood teams that tackle these adaptations rarely appreciate the difference between a comic book and a graphic novel, and generally approach them the same way.

Take Batman, for instance. This comic book character has been re-imagined several times on screen. Batman (1966) had a completely different feel than Tim Burton’s Batman, and the Nolan “Dark Knight” trilogy is far darker than its predecessors. Each of these comic book movies are valid interpretations of their source material as they all follow the Batman origin story faithfully. They play by the same rules that a comic book author most follow, and because of that find success.

This generally is not the case with graphic novels. The essential problem that arises when a team attempts a graphic novel adaptation lies in this: they fight the source material rather than embrace it.

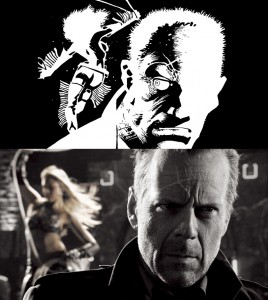

Now I’m not saying that a graphic novel film adaptation needs to be a straight panel-to-frame translation a’ la Sin City. This is both creatively stifling for the film makers and unrealistic due to time constraints. However, unlike a comic book movie that allows the screenwriters, directors, and visual effects artists to fully play so that they can create a brand new tale, the adaptors of graphic novel films are attempting to translate a complex and fully realized story to a new medium. I would say an apt comparison would be when a film adaptation of a novel is attempted, but that wouldn’t be acknowledging the existence of meticulously conceived, gorgeous images that accompany the words of a graphic novel.

The graphic novel author is not just writing a story; this talented individual is also plotting out panel-by-panel break downs of the dialogue, action, scenery, and environments that the artists will later be creating. When Alan Moore initially composed Watchmen, he did so with such vividness that made it easy for artist Dave Gibbons to understand exactly what was desired in every panel. Naturally, artistic revisions were made to create the fully realized masterpiece, but the fact remains that Moore was the initial force behind every element you experience when reading the classic work.

While a standard author is also able to create a stunning mental image through the sheer power of their words, those images ultimately float inside the head of each individual reader. How I picture the island from The Lord of the Flies will likely be nothing like how you will, and my mental image of Holden Caulfield that resembles Jake Gyllenhaal circa Donnie Darko probably doesn’t mirror yours either.

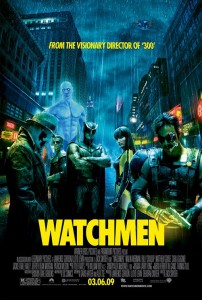

This isn’t the case with a graphic novel. When adapting one of these texts to film, every member of the team needs to know that any person who picks up the source material will have a very strict idea of how each scene of the story was meant to look. I know the look Dr. Manhattan gives before he vanishes to Mars, I know how quickly the camera is meant to pan while we watch cars drive around Sin City, and I know exactly how ripped Leonidas’ chest is meant to be. This is why the sense of expectation when viewing a graphic novel movie is so heightened; we know what to expect so thoroughly that you have to labor twice as hard just to avoid disappointing us.

Jonah Hex, V for Vendetta, 300, and Watchmen are each examples of films that left comic geeks wanting (and I’m not even referring to the fact that each of these movies to varying extents changed key elements of the plot lines from the source material that essentially nullified the very point the book’s author was trying to make). By over thinking the reimaging and neglecting the powerful road map they literally had at their fingertips, each of the filmmaking teams lost the magic of the original in a wholly disappointing way.

Jonah Hex, V for Vendetta, 300, and Watchmen are each examples of films that left comic geeks wanting (and I’m not even referring to the fact that each of these movies to varying extents changed key elements of the plot lines from the source material that essentially nullified the very point the book’s author was trying to make). By over thinking the reimaging and neglecting the powerful road map they literally had at their fingertips, each of the filmmaking teams lost the magic of the original in a wholly disappointing way.

When Robert Rodriguez was filming Sin City he famously worked hand-in-hand with Frank Miller himself. Miller has stated that amid his eagerness to play in the new medium of film he wanted to rethink some of his classic images from his books. It was Rodriguez who told him that his book had it right in the first place, and told him that they were going to use it as their ultimate guideline. This is the simple, respectful mentality that future graphic novel adaptors need to grasp. Rodriguez gets it. Now the rest of Hollywood needs to catch up.

Add comment